Glenfinnan viaduct - world's first mass concrete structure(?)

Glenfinnan Viaduct, Scotland: the world's first mass concrete structure?

Glenfinnan Viaduct, Scotland: the world's first mass concrete structure?The Glenfinnan viaduct in Scotland was completed in 1898; the piers and arches were built in concrete, without reinforcement, and many claim it to be the world's first major mass concrete structure - well, since Roman times anyway. It carries the West Highland railway line on its final stretch between Fort William, some 20 miles to the East, and the fishing port of Mallaig - this line is widely regarded as providing one of the great scenic railway journeys of the world. The Glenfinnan viaduct is not the only viaduct on the line but it is the largest.

The Glenfinnan viaduct viewed from the train, and the Glenfinnan monument.

The Glenfinnan viaduct viewed from the train, and the Glenfinnan monument.My wife and I have crossed the viaduct many times on the train, but never seen it close up from below. Last month, while on a "working holiday" in Scotland, we decided to pay it a visit. As we approached, the sound of the river Finnan rushing down to Loch Shiel echoed from the massive dark grey concrete arches. The evocative smells of bog myrtle and heather were carried on the strengthening wind, as were ominous dark grey clouds heading straight for us. Glenfinnan might be a small glen (glen=valley) but the scenery is superb, the viaduct is massive and the sense of history overpowering.

Built on a curve with an 800 feet (250m) radius, it has 21 arches each 50 feet (15m) wide, is 1248 feet (380m) long and 100 feet (30m) high and is 18 feet (6m) wide at the top between the parapets. From the top (best viewed from a train as there is no footpath) there are splendid views of the hills to the North and Loch Shiel and the Glenfinnan monument to the South; the monument commemorates the raising of Bonnie Prince Charlie's standard in 1745 - see historical note below).

Glenfinnan viaduct, distant view with hills to the North.

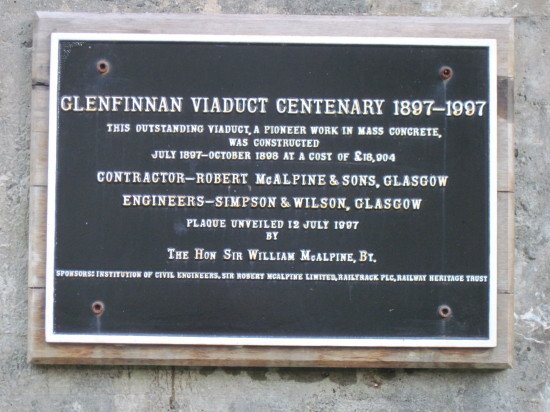

Glenfinnan viaduct, distant view with hills to the North. Glenfinnan viaduct: plaque on an arch celebrating the viaduct's centenary.

Glenfinnan viaduct: plaque on an arch celebrating the viaduct's centenary. Glenfinnan viaduct: impressions of wooden formwork, and lime - now carbonated to form calcium carbonate - leached from the arch.

Glenfinnan viaduct: impressions of wooden formwork, and lime - now carbonated to form calcium carbonate - leached from the arch. Glenfinnan viaduct, detailed view of formwork impressions.

Glenfinnan viaduct, detailed view of formwork impressions.The cost on the plaque is given as 18,904 British pounds in 1897. According to www.measuringworth.com (a most interesting site for calculating historical values and more) this represents 16.9M pounds today, based on share of Gross Domestic Product. Even that seems cheap; it would buy less than a mile of motorway, say 1 km. If it had to be replaced now with a similar structure, I suspect the actual cost would be much higher.

Until relatively recently, the trains crossing the Glenfinnan viaduct heading south carried fish from Mallaig. When the line opened, fish landed at Mallaig could be on sale in London next day. Now, with greatly-improved roads, fish and shellfish are taken by refrigerated lorry, much of the catch going to continental Europe ("they see the world...").

Today, there are up to four or five passenger trains each way between Fort William and Mallaig every day (fewer on Sundays and in Winter), providing a service to the local community and an unforgettable scenic experience to tourists. In addition, the Jacobite steam train runs in the summer. However, most people worldwide will know the viaduct (and steam train) from its starring role in some of the Harry Potter films.

A few miles up the line towards Mallaig is another viaduct, the Loch nan Uamh viaduct. During construction of a viaduct somewhere on the railway, a horse and cart had fallen into one of the piers but it was not known until recently which one, although the Glenfinnan viaduct was generally assumed. However, radar imaging of the centre pier of the Loch nan Uamh viaduct in 2001 showed clear images of a horse and cart. The driver apparently survived.

Glenfinnan Viaduct: a Historical Diversion (non-cementitious, skip this bit if you like):

The monument was built in 1815, seventy years after Bonnie Prince Charlie, otherwise known as Prince Charles Edward Stuart, raised his standard starting the Jacobite rising in 1745 - the '45 rebellion. The background to the rebellion, though, goes back much further, to 1603 and and the death of England's Queen Elizabeth I. Elizabeth, "the Virgin Queen", had no direct descendant as heir to the English throne. James VI of Scotland was her nearest relative of royal blood and became James I of England. The important point here is that James I/VI was a Stuart; now we need to follow the sequence of Kings and Queens.

Compressing and simplifying this fascinating, turbulent and bloody period of English and Scottish history - this is a cement blog, after all - in the 1740s, Prince Charles Edward Stuart was laying claim to the English and Scottish thrones. Nearly 100 years earlier, James I's son Charles I, had been executed by the Parliamentarians at the end of the English Civil war in 1649, and the monarchy overthrown. In 1660, the monarchy was restored, but its power was considerably limited by Parliament. Charles II, son of Charles I, was invited back as king and, when he died in 1685, his brother, James II succeeded him. However, James was a Catholic and he persecuted the Protestants and was unpopular. James was deposed when leading parliamentarians invited the Dutch prince William of Orange and his wife Mary (daughter of James, but a protestant) to rule instead.

After William and Mary, another of James II's daughters, Anne, became queen in 1702 and died in 1714, to be succeeded by George I, of Hanover. In 1727, George I died, and was succeeded by his son, George II.

Now we get back to Bonnie Prince Charlie, living in exile in Rome. The Jacobites (named after the Latin Jacobus, meaning James) wanted to restore the Stuart kings. They had strong Catholic support, but also much support from those in England, Scotland and Ireland who felt the deposition by parliament of James II to have been illegal, and from some Scottish Clans, from Spain and, of course, from England's traditional enemy, France. Prince Charlie was the grandson of James II and, if you believed in the divine right of kings to rule, deriving their authority solely from God, he was the lawful heir to the thrones of England and Scotland and of the kingdom of Ireland. Parliament had had no right to interfere.

Bonnie Prince Charlie travelled to France where he had been promised support. For various practical and political reasons, French support proved minimal and he landed in Scotland in 1745, where he had to raise an army from scratch. Initially successful, he defeated a government army at the battle of Prestonpans and marched south with his army towards London, reaching Derby. Unaware of the panic he was causing in London only 130 miles (200 km) away (the monarchy was packing to escape to the continent), Charles and his officers considered their next move. It was clear they had not received the support they had expected from English Jacobites and they were probably also discouraged by government-inspired disinformation about the strength of government forces. They withdrew back to Scotland.

In April 1746, Charles' Jacobite army was destroyed by a government army led by the Duke of Cumberland ("Butcher" Cumberland), son of George II, at the battle of Culloden, near Inverness. Charles eventually escaped and lived in exile in France and Italy, but his followers were less fortunate. Survivors of the battle were hunted down; even the injured who made it to Inverness and were being treated for their wounds in a church were shown no mercy. On a wider scale, the clan system was repressed; the Scottish language (Gaelic) was outlawed, as was traditional dress.

Life in the Scottish Highlands was hard at the best of times for most of the people; with systematic official persecution, it must have been a lot harder. Even worse was to come; later in the 18th century and the 19th, the Highland landowners found sheep or industrial activity to be more profitable than people on their land. The populations of whole villages were forcibly removed and their houses destroyed; the people were either homeless, or if they were offered an alternative place to live, the land was often insufficiently fertile to grow crops. Many thousands emigrated; in the long term, Scotland's loss was the gain of America, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and other destinations. In the shorter term, there was persecution, misery and starvation, with families separated for ever.

Today, anyone walking in the Scottish Highlands will come across the scattered remains of the Highland Clearances in the form of ruined individual houses or whole villages - often now just piles of stones.

So, Glenfinnan, this lovely glen in the West of Scotland, has a monument to a failed uprising - an uprising that almost succeeded and, had it done so, may have altered European and even World history. It has ruined cottages in the hills as monuments to vanished communities, and it has this wonderful viaduct. When it was built, the viaduct too was a monument - to what could be achieved with concrete. For people who had suffered years, or centuries, of marginal existence, upheaval and displacement, as they entered the new century the newly-completed viaduct and railway must have represented fresh hope.

Is it the oldest? Do you have another nomination?

As to whether the Glenfinnan viaduct is the oldest mass concrete structure in modern times, I really don't know, but I suspect the answer will depend in part on technical definitions and local allegiances. For example, another viaduct, the Hockley viaduct near Winchester in Southern England (1891) predates the Glenfinnan viaduct by a few years; it has piers made of mass concrete (brick-faced), but I understand the arches are brick, not concrete. I would be surprised if there weren't also some other candidates from France, Germany, the USA and other places. Ideas, anyone? We need some rules: I suggest the structure must be significant (ie: big and expensive to construct) and built entirely, or almost entirely, of mass concrete, sorry, Hockley. (I foresee scope here for varying interpretations of "almost entirely," "big" and "expensive"...)

We may need more than one category:

a) ancient, ie: pre-6th century (the Pantheon roof is concrete, but the pillars are granite)

b) anything circa 6th century - circa 18th century

c) industrial revolution containing Portland cement or similar (must be pre-1898 to beat the Glenfinnan viaduct).

Send in your suggestions using the web site Contact Form!

Back to our walk - by now, we could see the sheets of rain coming nearer and we headed back to the car a quarter of a mile down the track. My wife had been blown off her feet in a gale on the summit of a hill the day before, and this was an unplanned stop at the Glenfinnan viaduct on our return journey from the casualty department at Fort William hospital. Her arm - now known to be fractured - had just been set in plaster by the efficient and caring medical staff. Without her fortitude in adversity, and enthusiasm to see the viaduct, this visit and blog entry would not have been possible.

Well, this is only my first blog item and I've already mentioned the taboo subjects of politics and religion, even though the events were a quarter of a millenium ago. Let's just hope this blog improves.

Glenfinnan viaduct, western end, looking South.

Glenfinnan viaduct, western end, looking South.22nd November 2010

Exit Glenfinnan viaduct blog page and return to the main blog page

Check the Article Directory for more articles on this or related topics